The Livable City

Pegah Jalaly

Senior Architectural Designer

BAM Creative, New York

Introduction

Urban design and planning date back to the beginning of human civilization. Cities first formed after the Neolithic Revolution, which brought agriculture and made denser human populations possible, thereby supporting urban development. Urban design has come a long way since then and a variety of city planning strategies have emerged overtime. The common denominator among all these developments is the response to human needs during different historical periods. Although the first step in shaping each of these urban planning approaches was manifested in the city's appearance and spatial organization, many complex layers were added during the life span of a city. These nonmaterial layers are shaped by culture, economy, and social values and are also entangled with an urban community's needs. These needs have become more complex and harder to define as societies grow and develop over time.

Urban design and planning date back to the beginning of human civilization. Cities first formed after the Neolithic Revolution, which brought agriculture and made denser human populations possible, thereby supporting urban development. Urban design has come a long way since then and a variety of city planning strategies have emerged overtime. The common denominator among all these developments is the response to human needs during different historical periods. Although the first step in shaping each of these urban planning approaches was manifested in the city's appearance and spatial organization, many complex layers were added during the life span of a city. These nonmaterial layers are shaped by culture, economy, and social values and are also entangled with an urban community's needs. These needs have become more complex and harder to define as societies grow and develop over time.

Designating communities’ current needs is the first step towards creating a desirable environment, a livable city. The livable city is a community-oriented space that results from dense, authentic, and engaging urban environments. The integrated network of human relationship with the public environment creates the soul of a city. Such a spirit will define the city’s character and determine whether its civic platform really is livable.

To better understand the multifaceted relationship between humans and cities, and to dig further into the concept of a livable city, it is helpful to glance over the history of urban design and compare it with today’s conditions. Studying narratives, strength and weakness, success and failure of what has already been implemented will bring to light the fact that such an ideal context will only be obtained when all of society contributes to its development. For that reason, business owners and developers play a significant role in the process of creating a livable city.

An Overview of UrbanDevelopment History

Why The Need To Review The Past

Modern viewpoints about city and community planning have their precedents in the city’s historical development and in the theories presented by designers and planners over centuries about how responsible evolution of the land can improve people’s lives. Knowing the history of urban planning helps comprehend how a building project is connected to the community and city in which it is located.

Early Cities, The Answer To Basic Needs Of Settled Humans.

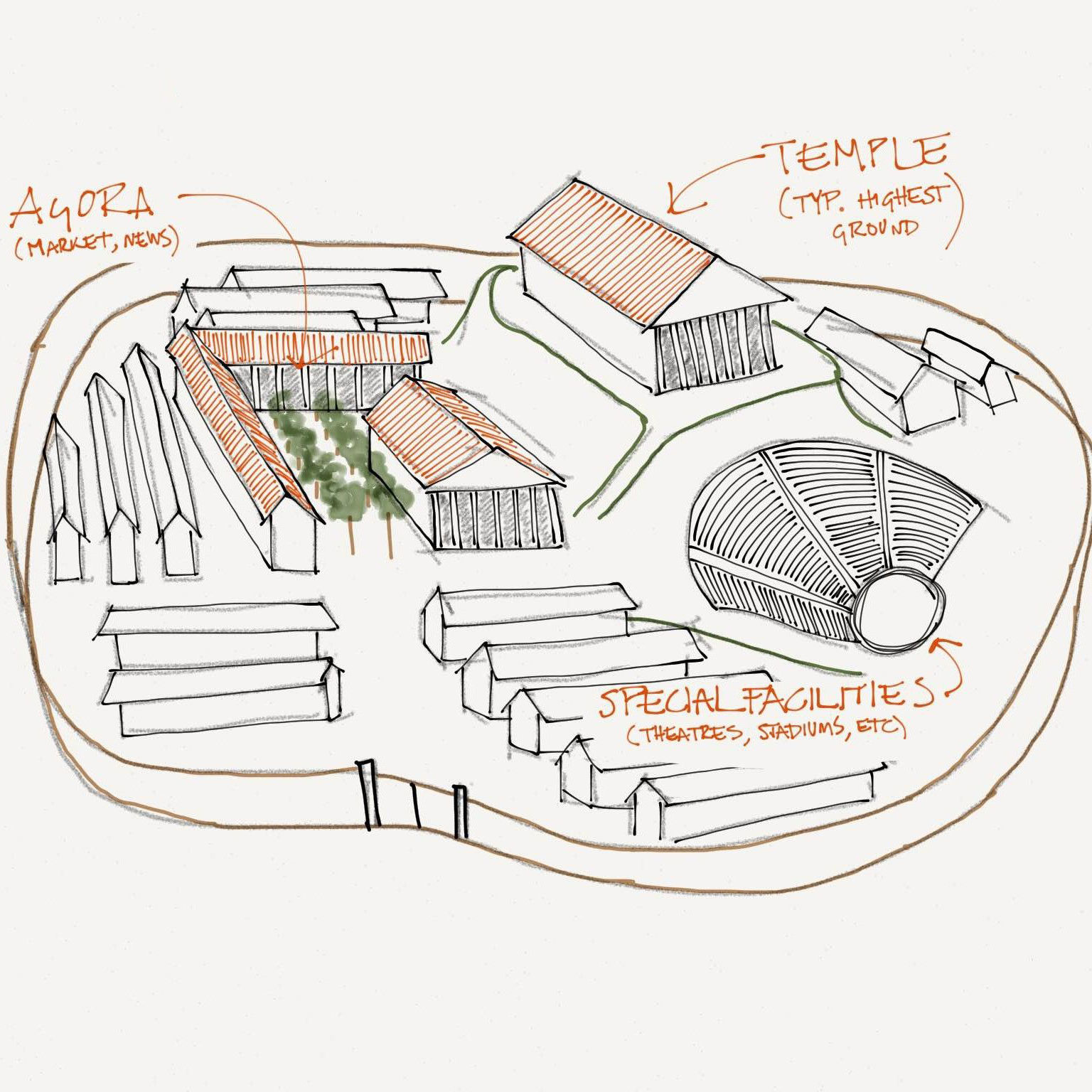

In the earliest settlements, life and living quarters were pivoted around central buildings, including the granary, where food was stored, and the temple, which had multiple functions. The temple was used not only to conduct the village’s administration, but was also a place for ceremonies, social interaction, and trade. Gradually other needs started to emerge including security and entertainment. Urbanites needed to feel secure against any threat coming from outside of their community, and they also needed to have entertaining activities besides their daily routines. Ancient Greek cities responded to these demands: They were encased by security walls and had special facilities, such as theaters and stadiums, for leisure. With a little contemplation on this arrangement, we can see that this primitive form of a city was a response to the most immediate human needs at the time, which interestingly were not limited to defense or overcoming hunger, but considered the necessity for having a public space to gather, socialize, and interact.

Medieval and ancient Greek cities were primary forms of urban design responding to the basic needs of settled humans.

Integration Of Art And Cities: A Call For Living In Beauty.

During the Renaissance, city planning took on greater importance. Although military and defense considerations were still remarkable, planners paid more attention to urban design aesthetics. City plans combined symmetrical order with the radial layout of streets that centered on focal points. The radial boulevards’ primary organization was over-laid on a grid of secondary streets or over an existing road system. The idea of giving the city an orderly and rational form, making it a symbol of the artistic and philosophical conception of the whole Renaissance, slowly matured in the works of fifteenth-century urbanism. Centuries later, this idea was still appealing: Nineteenth-century Paris is a case in point where planners advocated straight, arterial boulevards connecting principal historic buildings, monuments, and open squares. The plan was intended to minimize riots and clear out slums but also succeeded in beautifying the city.

The Renaissance brought art and beauty to the cities to meet the citizens' need for aesthetics.

The Industrial Revolution & A Fundamental Change In The Design Of Cities.

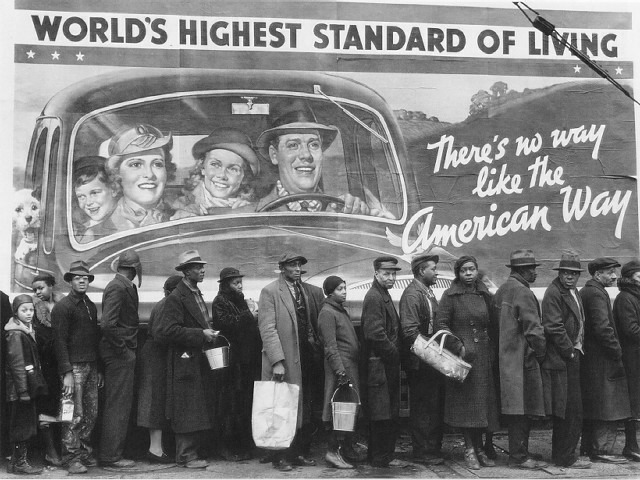

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and following the Industrial Revolution, the focus of city-building turned to increasing goods production, rather than on social or aesthetic interests. As a result of this shift in values, cities soon became overcrowded, filthy, and empty of open space and recreational activities. The factory system required that the workforce be close to the factory in addition to requiring transportation and distribution outlets. As production expanded, so did the populations of factory towns. The unhealthy and depressing living conditions imposed on people by the industrial revolution ignited a reform movement to improve housing conditions, water supply, and sewage systems, to provide sanitation, reduce crowding and above all, to realize the need for open space and recreation.

During the Industrial Revolution, the goal was to maximize production and profit-making; Life in the cities of the Industrial Revolution was difficult for most people, especially working-class groups.

Zoning, Segregation & Urban Sprawl

One of the most famous reform movement results was the garden city notion, an attempt to create a town-country context. In this strategy and some other reforming city plans, separate zones for residential, public, industrial, and agricultural linked by a separate vehicular circulation path were proposed. This idea influenced several famous designers and planners such as Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier, who envisioned cities with vast open spaces. Their theories started impacting cities’ characters to the point that the suburb became a dominant city form in the twentieth century. Suburbs were developed to escape crowding and other negative aspects of the center city. In the U.S., when the population increased after World War II, the suburbs boomed as more and more people wanted the advantages of space, fresh air, light, and a desirable place to raise a family. As greater numbers of people wanted to move to the suburbs, individual plot sizes became smaller, and developments sprang up farther from the city. The suburban house with a small yard became a tiny version of the idealized country property. As the suburbs grew, so did the call for an even larger network of highways to serve them and shopping centers to provide necessary services. What became known as urban sprawl soon followed. .

A City For Today.The Need Of Our Time.

Lessons To Learn From Past Failures

The booming automobile industry, plus the desire to live away from the cities—while still having access to them for work—resulted in an uncontrolled development of roads and highways, and cities became very car-oriented. So did people’s lifestyle. Additionally, the real estate market became another factor in pushing people out of the cities. Middle-class families fled to the suburbs to own a reasonable property to raise a family. At the same time, working-class people were pushed to ghettos or so-called affordable housing projects. Consequently, the process of Urban Renewal turned many cities into segregated areas of expensive business districts filled with buildings and streets: “Many postwar downtowns became dead zones outside the 9-to-5 working hours since there was little left other than office buildings and commuter parking lots, which were more profitable for developers than the retail and apartment buildings of yore” (How America Killed Transit-SmartCities-2018).

Following World War II, and continuing into the early 1970s, “urban renewal” referred primarily to public efforts to revitalize aging and decaying inner cities.

Such a pattern caused many social and environmental problems such as urban sprawl, reliance on the automobile, environmental deterioration, housing segregation, single-use development, and very importantly, lack of public or semipublic areas for people to gather and socialize. The absence of pedestrian-friendly neighborhoods and open spaces for people to connect to their environment and build their daily interactions, as well as the lack of vitality and excitement of a city that has evolved over time, contributed to the failure of post-war urban planning strategies. As Jane Jacob stated in her book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities-1961, “There is a quality even meaner than outright ugliness or disorder, and this meaner quality is the dishonest mask of pretended order, achieved by ignoring or suppressing the real order that is struggling to exist and to be served.”

New Urbanism: Reclaiming Streets, Reclaiming Cities.

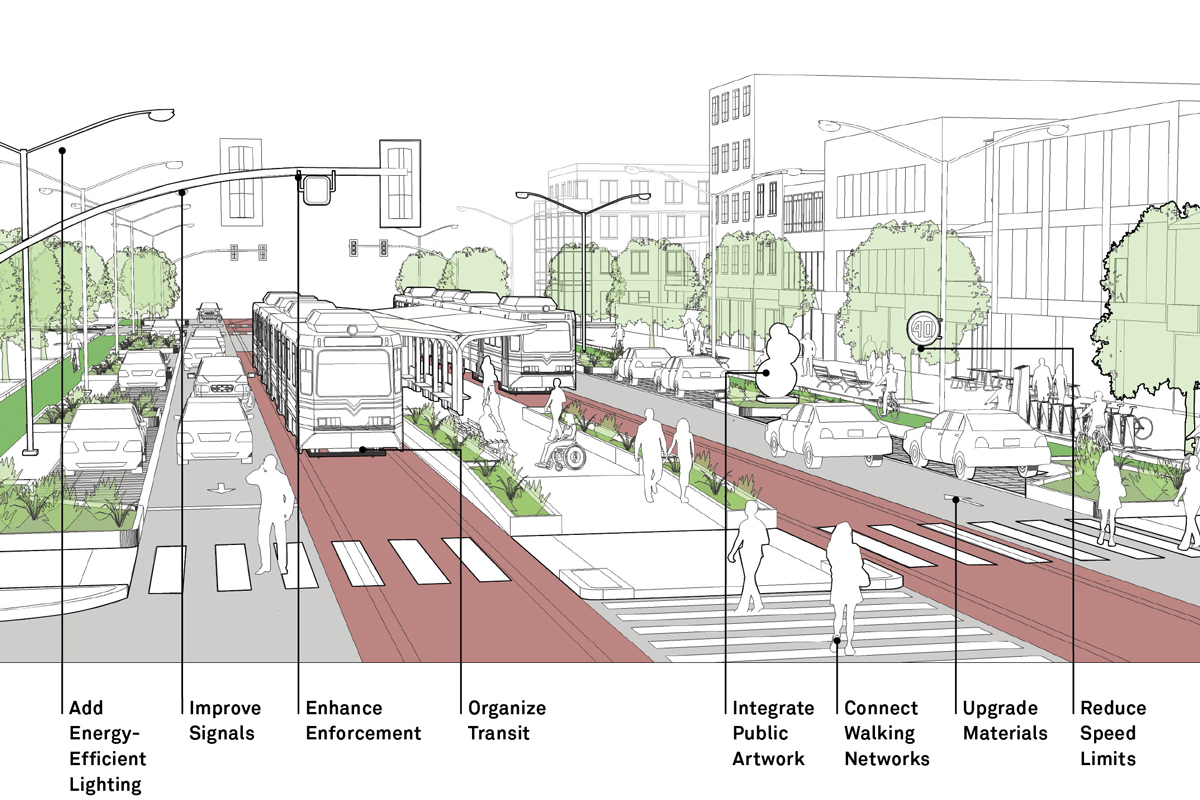

As an acknowledgment of problems emerging from previous urban development methods, New Urbanism planning concepts are planned to work at different scales, including the building, neighborhood, district, and region. The essence of this system is the development of neighborhoods intended for mixed-usage: housing located within walking distance of shops, offices, and other services, and a variety of residential accommodations, from apartments above shops to single-family houses and the integration of civic, institutional, and educational facilities into neighborhoods. At other levels, New Urbanism supports the connection of neighborhoods and towns to regional patterns of the pedestrian, bicycle, and public transit systems while reducing dependence on the automobile and setting connections to open space and natural systems.

The mixed-use neighborhood, pedestrian, and bicycle friendly layout, and access to public transportation, are among the main features of New Urbanism to reclaim urban areas.

Even though New Urbanism is a contemporary idea of planning cities, its principles have motivated social movements throughout history. For instance, Reclaim the Streets, a movement about community ownership of public spaces, which opposes the car as the ruling mode of transport, started in the late 1980s in London, U.K., and gradually spread around the world. Also, various events and activities taking place in the streets, from large festivals, such as Summer Street in New York City, to small block parties in any neighborhood, can be categorized as efforts for promoting the importance of a vibrant, mixed-use, and pedestrian-friendly urban environment.

“New Urbanism” follows the same values as some other urban/social movements such as “Reclaim the Streets,” with an emphasize on ‘humanizing’ the urban environment and dedicating more space to the pedestrians in a community-oriented setting.

2020: Covid-19 And Cities.

Perhaps in no other time in modern history than in the immediate last year, a small park in the neighborhood, few steps in front of the entrance door, or even an old bench on the sidewalk has looked so precious and valuable in the eyes of those who have been stuck in their homes for months to save lives of others and their own. Living in such an unprecedented time has revealed the need for a self-sufficient district offering pedestrian access to services and recreation within walking distances more than ever. It also brought up the necessity of sufficient outdoor public spaces for distanced and safe socializing and leisurely activities.

In cities like New York, the experience of outdoor eating zones taking over streets and car parking spaces was not only a solution for bars and restaurants to survive during the pandemic, but also an opportunity for people to see the beauty of a dynamic outdoor urban life and to pay attention to the kind of lifestyle they have been missing out on in exchange for car-dominated streets and real estate.

“Some cities are looking to the unintended benefit of this pandemic as an opportunity for reforming their living contexts.

Role Of Business Owners And Developers In Making A Livable City.

Responsible Development

Human societies today need a vibrant, community-oriented urban environment. To achieve this purpose, a universal effort to shift from urban sprawl to adaptive reuse and creating dense, integrated urban areas is an urgent matter. To make a city livable and responsive to a community’s needs, it is necessary to bring people, activities, buildings, and public spaces together, with easy walking and cycling connections between them and a reliable transit service link to the rest of the city. At the core of this movement, developers and business owners can play a vital role by immersing a building project in the community and city where it is located. The environment affects how a site is developed and how a building is designed; the building, in turn, affects the larger community of which it is a part. Developers can positively impact this process by choosing a responsible development to prioritize issues like quality, community, security, and sustainability, over pure profitability.

A compact and integrated urban context can help shape a healthy, vibrant community.

Site Selection

As the need for adaptive reuse and repositioning increases, single-use developments such as shopping malls, industrial complexes, corporate offices, and university campuses are rearranged into walkable, mixed-use communities. Several cities worldwide, such as New York City, benefit from the successful approach of combining old manufacturing and light industrial uses with live-work residential spaces, entertainment functions, and retail. Respecting such a strategy, redeveloping available sites within an urban context instead of purchasing a greenfield or selecting a site in an isolated business or industrial zone, is the practical approach to ensure that the community is positively affected. Redevelopment of an existing urban fabric helps ensure that residents can live close to jobs, schools, services, and other destinations, resulting in reduced travel time and environmental pollution.

In addition to the idea of mixed-use and local developments, accessibility of a site also plays an important role in shaping a Livable City where walking, bicycling, and public transit are the most efficient choices for traveling. The importance of a non-car-oriented development and site selection is even more crucial when thinking about how it allows for flexibility of public space when needed, as evident during the pandemic.

A Flexible Development

One of the impacts that the recent pandemic will potentially have on future developments is planning for flexibility. This can include changing the use and increasing the capacity of spaces, such as a neighborhood or a city block, and to have enough adjustability to expand their performance to a larger scale. For instance, during the pandemic, many car spaces around NYC converted to outdoor seating and dining areas, which allowed bars and restaurants to function and provide a safe environment for people to maintain their urban lifestyle. Developing properties with smaller building footprints and larger open spaces can be considered as one of the ways to contribute to a flexible development that is open to meeting potential future needs.

Developments in a city should aimed at serving communities at different times and under different conditions.

Why Should Developers Consider The Path Toward Creation Of The Livable City

Responsible development can balance short-term gains with long-term needs. Construction projects can have achievements beyond financial profitability in a short time if planned in a way to positively contribute to the economic, physical, and social aspects of an existing community. Socially and environmentally sustainable developments can be advantageous for the project and the context in which it is placed in a variety of ways, as discussed below.

Governments and city officials support several urban planning strategies to promote the idea of a responsible development through rewarding developers with incentive zoning that allows them to build larger, higher-density projects or a different land use than existing zoning permits. For example, Transit-Oriented Development is a type of urban development that maximizes residential, business, and leisure space within walking distance of public transport. It promotes a symbiotic relationship between dense, compact urban form and public transport use.

Transit Oriented Development (TOD) is a type of development that includes a mixture of housing, office, retail or other amenities in a walkable pattern located within ½ mile of quality public transportation.

Another important issue that this type of development will address is security. As Oscar Newman outlines in his defensible space theory, giving control and responsibility to community will greatly protect a neighborhood against crimes. A mixed-use neighborhood is not quiet nor inactive at any time of the day. Consequently, it will provide natural and constant surveillance by users of the space in any neighborhood. There will be eyes on the street and the buildings all the time, which is one of the most effective ways of crime prevention. Environmental benefits can be counted as another significant impact of New Urbanism and what is referred to as the Livable City. While climate change and the environmental crisis threaten human future, a global movement at all levels of society is critical to facing and overcoming this challenge. Walkable communities with high-quality public transportation can create low carbon lifestyles by enabling people to live, work, and relax without depending on a car for mobility. This type of lifestyle can reduce energy consumption and commuting time significantly.

“A walkable, self-sufficient neighborhood can provide a range of community and individual benefits, from reduced time spent traveling to work, improved walkability, access to amenities, and lowered transportation costs.

Finally, high-quality work environment lead to an increase in employees’ efficiency and productivity. This quality is not limited to the actual building or layout of a workplace, but with a higher proportion depends on the environment in which the workplace is located. People need diverse and stimulating environments. In a monotonous urban setting, community, or building, people suffer from negative influence, such as becoming depressed or irritated. Through thoughtful developments, the city can be a place that promotes social interaction. By providing spaces to gather, see other people, cross paths, and meet informally, a vital aspect of human life can be addressed. Experiencing a dynamic and lively neighborhood can motivate people to leave their residence to connect with their urban environment. As a result, the quality of people’s participation in their communities will increase while being in places other than their homes, including their workplaces.

“High-quality urban context can promote social interaction and motivate people to come out of their residences and go to work.

Conclusion

Over the span of decades, rather over centuries, there has been a constant morphosis of cities and how they are planned and developed based on the requirements and needs of a society. For example, defense in the Medieval era, beauty and order in the Renaissance era, and maximizing goods production during the Industrial Revolution were all major demands and goals that needed to be achieved while planning for development of cities in those time periods.

Strong economic outcomes are vital and can be considered a significant necessity in any business model. However, there are many ways to achieve strong economic outcomes, including destructive ones which harm a community in the long run. For many years the economic successes of the Industrial Revolution, the automobile industry, and the real estate market, have driven developments and shaped cities. Focusing on profitability without a broader and deeper vision about community needs, however, has exposed many societies to various problems such as urban sprawl, segregation, and car-dominated lifestyles. These unwanted impacts can result in an unhealthy urban context, followed by a troubled community.

After facing the consequences of failed methods from the past and with the current pandemic continuing to highlight the absence of critical spaces that a community needs, the urgency to revisit the concept of urban development is even more important. In the new approach, the focus on healthy communities is the foundation of creating and maintaining economic activity. Robust communities result from dense but authentic, and attractive urban environments with a network of capabilities that create diversity.

There is an undeniable role of developers and business owners to evolve and emphasize new strategies in support of communities. While balancing short-term gains with what is needed long-term for a thriving living environment, they can offer positive alternatives for society. Responsible developments will result in achievements for business owners and for the community at large. Maintaining such a mindset while making decisions about where to develop a project and how to develop a project can be strongly effective in creating the Livable City.

Lively and vibrant cities are vital for their occupants and businesses to survive and grow. After all, what gives a city its soul and makes it livable is a network of people, community, activities, and complex layers of integrated relationship and connections within an urban context; otherwise, it will only be a collection of massive buildings and wide roads with no life or values.

There is no logic that can be superimposed on the city; people make it, and it is to them, not buildings, that we must fit our plans.

Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities-1961